Written By: Geetha Moorthy

I have a soft spot for Sri Lanka. It’s the place I was born and where I spent my formative years. I had the privilege of going to school in the picturesque tea hills of Kandy; performing across the country as a classically trained dancer; and working in the burgeoning metropolis of Colombo. Unfortunately, my family was forced to flee in the 1980s as the country began to descend into civil war. The silver lining, of course, was that we found a new home in Canada as did so many other Tamil families that fled Sri Lanka in the 80s and 90s in search of refuge and peace. It made sense that the first families we served as an organization and the first volunteers we had were from this community. We had a collective history of forced migration and shared values, cuisine, arts and language.

It also made sense that SAAAC’s first foray into work outside of Canada’s borders would be Sri Lanka. The SJC Initiative, a non-profit working in the Killinochi area to improve education in the aftermath of the civil war, approached us in 2018 with a project that felt serendipitous. Killinochi region was one of the areas most disproportionately impacted by the Sri Lankan Civil War that ended in 2009. SJ’s work in the immediate aftermath of the war with little formal organizational structure was admirable. After a few discussions we quickly realized they would be a perfect partner for SAAAC’s first international endeavor.

After extensive planning and the support of the SJC Initiative we set-off on our first trip overseas to conduct a needs assessment of the special needs education system in Killinochi in October 2019. During our brief 2-week visit, relying on the goodwill built by our partners, we were able to visit 17 different schools across Killinochi. We met with over 200 students, parents, teachers, and administrators right up to the highest-ranking officials responsible for education at the district level. This access allowed us to have a bird’s eye view of the special needs education system from different perspectives.

But still, connecting with a population reeling from the impacts of war presented its own challenges. The trauma was palpable and PTSD felt like it was the default setting for everyone we encountered. Our group of five volunteers that made up the SAAAC team were all Tamil-Canadians. We all had a collective history with the people of Killinochi. A collective history that is until that sharp point of divergence: we had all left by chance, fate or fortune but they had stayed. They experienced the brunt of a decades long armed conflict that we only read about in headlines. They experienced loss. We were aware of statistics and stories.

Although our paths and histories diverged, a shared language and culture were very helpful in connecting with this post-conflict special needs community in a meaningful way. Not requiring intermediaries for translation and interpretation created a safe space to share stories of loss, depravity and stigma. In two weeks, it felt like we had made valuable inroads into a community that so badly needed support.

And then we left.

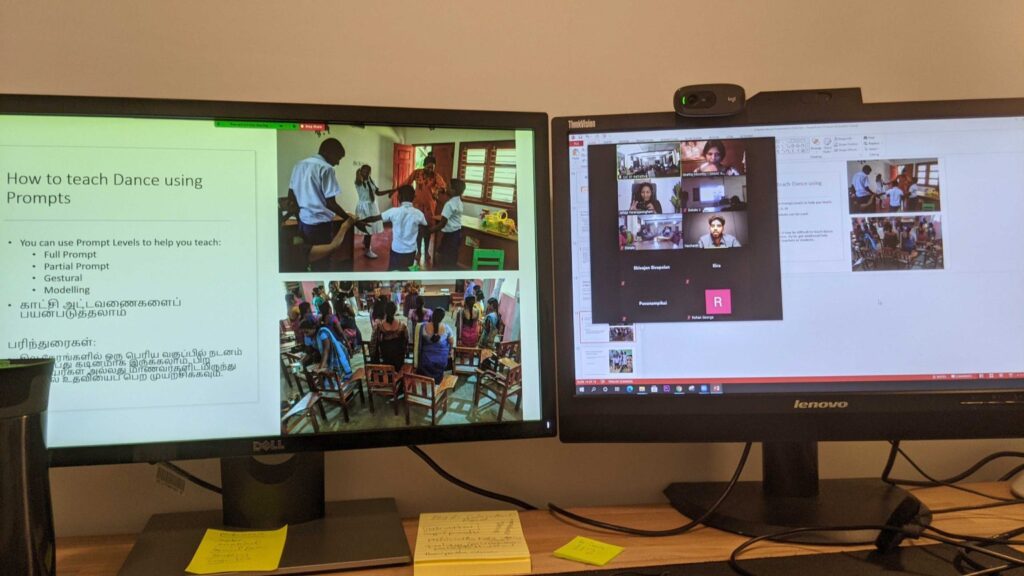

Upon returning to Canada, we completed our needs assessment report and began to make plans for implementing our recommendations on the next trip. That’s when COVID hit. We couldn’t go back. It felt like we had just been another NGO instilling hope that expired with our departure from the island. With no certainty of borders re-opening, we decided to turn to remote workshops for the special education teachers we had met and worked with. We decided to use Zoom.

For months we held training sessions via Zoom to try and distill our knowledge and experience working with special needs populations in Canada into practical workshops for special needs teachers on the ground in Killinochi. We held workshops on the basics of mental illness, communication strategies and incorporating arts into the classroom. Despite the frailties of online teaching and learning, I am humbled to report the sessions went well. The teachers are eagerly engaging with our training materials and facilitators and actively seeking out more information from us. They are eager to learn. We are eager to teach.

We run the sessions in the Tamil language utilizing volunteers from different academic disciplines. To see how a shared language can increase engagement in these sub-optimal settings is hard to describe. The best example would be from our last session on Dance and Functional Movement in the classroom. After sharing several theories, tips and activities on how to incorporate these in the classroom one of our volunteers said the phrase: neengal thaan santharpangalâai uruvaakanum. You have to create the opportunities for them. The looks of acknowledgement and understanding came across video over nine time zones and that spotty internet connection. Working with children with special needs didn’t mean finding the perfect lesson or resources but rather facilitating learning, creating opportunities and environments to foster learning. They understood.

There are limitations of course. But we have decided as an organization that we will continue to choose to light candles rather than curse the dark.